ENGLAND:

Call For a New Organ Donation Method

feature | April 2016

By Chiara Brambilla

WALES HAS RECENTLY INTRODUCED AN 'OPT-OUT' SYSTEM, INCREASING THE NUMBER OF ORGAN DONORS. WHAT WOULD SUCH A CHANGE MEAN TO ENGLAND?

Aaron Cavanagh was just 33 years old when he died; he was waiting for a lung transplant that never came.

His girlfriend Samantha Emma Brooker, 29, did not want his death to be in vain. Six months ago she decided to start a petition to make organ donation registration in England automatic. Parliament will respond to this proposal only if there will be 10,000 signatures, and so far it has managed to reach 9,441 and the deadline for the signature target is 27.

For Emma, his future was taken away from him as is the case with many others in England who die waiting. Around 10,000 people are on an organ waiting list in the UK and each year around 1,000 people die without receiving a transplant, according to the NHS Blood and Transplant Organisation.

There are currently two main laws regarding organ donation and transplantation in the UK: The Human Tissue Act 2006 applied in Scotland and The Human Tissue Act 2004 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

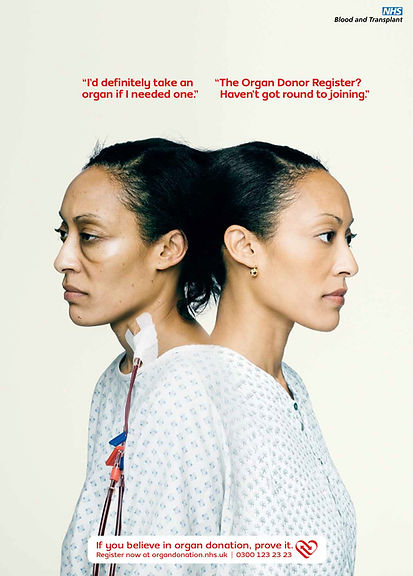

Under UK law, donors can ‘opt-in’ to the system, where a person has to express their consent to be a donor such as leaving a will, telling their relatives or friends, carrying a donor card or joining the NHS Organ Donation Register (ODR).

In December 2015 Wales became the first nation in the UK to change the system with a more avant-garde one: the “deemed consent” or the so-called ‘opt-out’ system. Under the new law, a person is automatically assumed to have given consent unless they had registered an objection in advance. Proponents believe this may raise the supply of organs’, saving more lives.

Several petitions have been already put forward by ordinary people who wants to follow Wales’ steps but so far they have not been taken up by Parliament.

Although the situation in England has improved since 2007 with a 50 per cent increase in the number of deceased donors and a 30.5 per cent increase in transplants in 2012/13, leading to 3,100 lives saved, a call for change is required.

“The NHS does what it can to improve the overall consent rates in the UK. They have limited funds so they do what they can,” says Nigel Burton, Vice Chairman of the ‘Donor Family Network’ (DFN) charity. “Without proper funding there is very little else they can do.”

The DFN charity’s aim is to encourage and support families of those who have died and donated as well as people who purely wants to join the ODR.

“We also try to raise awareness of organ donation issues through the media. The ‘Gift of Life Memorial’ opening last week had excellent media coverage,” he says.

In the years ahead UK organisations might actually achieve actual results with the continue use of promoting strategies. If this occurs, the successful case of Christopher Hughes will be just one of many.

Christopher was 44 years old when he received the gift of life. Van Assistant for the British Red Cross for over a year, Christopher has always put others before himself. “I have been signed up for 35 years [on the NHS Organ Donation list], never thought I'd need a transplant, I care about other people,” he says.

In January 2004, Christopher was taken ill, with flu symptoms but the truth was much harsher: his liver was not working properly. In April the situation was getting worse and he was then referred to the transplant team at the Queen Elisabeth Hospital in Birmingham. In August that year, he was matched with a donor with his same blood group, A+, have had a successful liver transplant, saving his life.

“Organ donors give people like myself so much. I’ve seen my son grow up, we have a beautiful two- and-a-half-years-old granddaughter,” he says. “I'm not a religious man but someone had an eye on me.”

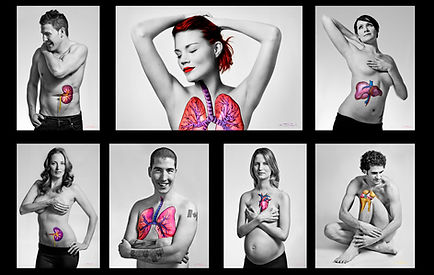

Yet, this is not always the case, as there are far more people on waiting lists than available organ, and even fewer with suitable matches. More than 500,000 people die each year in the UK but less than 5,000 die in circumstances where they can actually be donors, according to the NHS Blood and Transplant Organisation.

Professor Hugh McLachlan, professor of medical ethics and applied philosophy at Glasgow Caledonian University explains that there are ethical factors behind this lack of organ supply. “I think that doctors and other medical staff often reduce the number of available organs by heeding the views of the relatives of deceased and dying patients who have previously given consent to the use of their organs.”

The current laws allow the family to decide whether to donate a person’s organs at the moment of their death, regardless of whether the person had agreed to donate their organs while living.

“The wishes of the relatives of a dead or dying person should have no bearing on what happens to that person's body unless he or she has previously indicated that he wants them to have a bearing,” he says.

On the other hand, the emotional loss of a death of a relative means that any change of legislation may have to be handled sensitively to avoid further trauma on families. Most organ donors are the result of sudden deaths such as accidents or suicides, rather than people who are long term ill, because only healthy organs are suitable for transplant.

Katherine Gough, worker for the NHS, saw her mother saving the lives of five individuals, donating kidneys, corneas and liver. Katherine’s mother was 64 when she was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm; only few months later, they had to consider organ donation as there was no good outcome.

“I didn't know my mother was on the register,” Katherine says. “I don’t believe that you should go against someone's decision but having been there, I can see that the easier decision would be to say no at the time. However, the pride our whole family now feel really does make it feel like her death was not in vain.”